Of tantivy's indexing

This post is the second post of a series describing the inner workings of a rust search engine library called tantivy.

Foreword

In my last blog post, I talked about the data-structures that are used in a tantivy index, but I did not explain how indexes are actually built. In other words, how do you get from a file containing documents (possibly too big to fit in RAM) to the index described in my first post (possibly too big to fit in RAM too).

You may have noticed that index data representation is very compact. If you do not index positions nor store documents, an inverted index is in fact typically much smaller in size than the original data itself.

This compactness is great because this makes it possible to put a large portion, if not all, of the index in RAM. Unfortunately, compact structures like this are typically not very easy to modify:

Imagine you have indexed 10 millions documents, and you want to add a new document.

This new document will bear document id 10,000,000 For simplification, this document might contain for instance a single token, the word “rabbit”.

In order to add this new document, we need to add the document id 10,000,000 to the posting list associated with the word “rabbit”. No matter how optimized our algorithm is, this will require moving around all of the postings list coming after the one associated with the word “rabbit”.

Another problem is that tantivy is supposed to be designed to handle building an index that does not fit in RAM.

This blog post will explain in detail how this is done in tantivy…

A lot of small indexes called segments

Well, our problems are quite similar to sorting a list of integers that does not fit in RAM. In this all-time-favorite interview question, a common solution is to split the input file in more chewable chunks, sort the different parts independently, and merge the resulting parts. Tantivy’s indexing works in a similar fashion.

While my last post described a large single index, a tantivy index actually consists in several smaller pieces called segments.

If you went through tantivy’s tutorial, you may have noticed that after indexing Wikipedia, your index directory contains a bunch of files, and all of their filenames follow the pattern

SOME_UUID . SOME_EXTENSION

The UUID part identifies the segment the files belong too, while the extension identifies which datastructure is stored in the file (as described in the first post). Really, each segment contains all of the information to be a complete index, including its own entire term dictionary.

Segments, commits, and multithreading

While tantivy supports delete operations since version 0.3, I will not address deletes in this blog post, as they add a lot of complexity to the index.

Let’s assume we want to create a brand new index.

After defining our schema, and creating our brand new empty index, we need to add our documents. Tantivy is designed to ingest documents in large batches.

API wise, this is done by getting an IndexWriter,

and calling index_writer.add_document(doc) once for each document

of your batch, and finally call index_writer.commit() to finalize the batch.

Before calling .commit() none of your document is visible for search.

In fact, before calling .commit(), none of your documents are persisted either.

If a power surge happens while you are indexing some documents, or even during commit, your index will not be corrupted. Tantivy will restart in the state of your last successful commit.

Under the hood, when you call .add_document(...), your document is in fact just added to an indexing queue. As long as the queue is not saturated, the call should not block and return right away. Applications using tantivy are in charge of managing a journal if they want to ensure persistence for each insert.

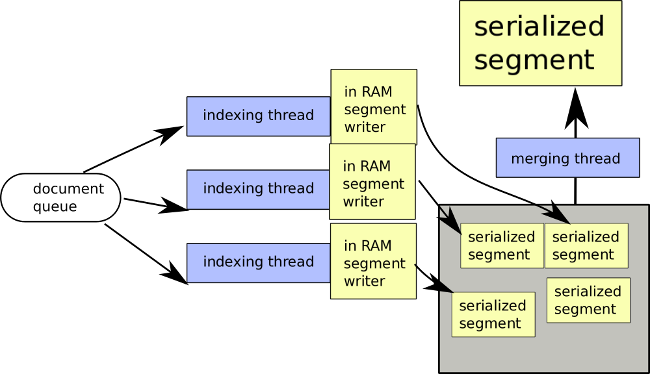

The index writer internally handles several indexing threads who are consuming this queue. Each thread is working on building its own little segment.

Eventually, one of the thread will pick your newly added document and add it to its segment. You have no control on which segment your document will be routed to.

These indexing threads are working in RAM and use very different data-structures than what was described in part 1, as they need to be writable. They are presented in details in the stacker section.

Every thread has a user-defined memory budget. Once this memory budget is about to be exceeded, the indexing thread automatically finalizes the segment: it stops processing documents and proceeds to serialize this in-RAM representation to the compact representation I described in my previous post.

The resulting segment has reached its final form, and none of its files will ever be modified. This strategy is often called write-one-read-many, or WORM.

At this point, your new documents are still not searchable.

Our fresh segment is internally called an uncommitted segment.

An uncommitted segment will not be used in search queries until the user calls .commit().

When you commit, your call blocks and all the documents that were added to the queue before the commit get processed by the indexing threads. All of the indexing threads get a signal that they need to finalize the segment they were building, regardless of their sizes.

Finally, all uncommitted segments become committed segments and your document is now searchable. Your commit call finally returns.

Search performance, the need for some merging

Having many small segments instead of a few larger segments has a negative impact on search IO time, search CPU time, and index size.

Assuming we are building an index with 10M documents, and our individual thread heap memory limit was producing segments of around 100K documents, indexing all of the documents would produce 100 segments. This is definitely too many.

For this reason, tantivy’s index_writer continuously considers opportunities to merge segments together. The strategy used by the index_writer is defined by a MergePolicy.

You can read about merge policies in Lucene in this blog post.

The merge policy by default in tantivy is called LogMergePolicy and was contributed by currymj.

It may be tempting to always try to have one single segment. In practice, if most of your index fits in RAM, as you merge segments, the benefit of having fewer segments will become less and less apparent. Having half a dozen of segments instead of having one big segment makes in practice very little difference.

Indexing Latency vs Throughput, search performance

As we explained adding a document, does not make it searchable right away.

You might be tempted to call .commit() very often in order to lower the time it takes for a document you added to become visible for search, aka the indexing latency of your search engine.

Please do this carefully as it as there are downsides to call .commit() frequently.

First, it will considerably hurt the indexing throughput. Second, by committing frequently, you will produce a lot of very small segments.

In other words, committing too often will hurt your indexing throughput considerably, as well as you search performance if the merge policy does not keep the number of segments low, and finally, it will raise the CPU time spent in merging segments.

Yet again we face the everlasting war of latency versus throughput.

Stacker datastructure

Now let’s talk a little bit about how the segments are built in RAM. I will not talk about how fast fields or stored fields are written, as their implementation is quite straightforward. Let’s focus on the inverted index instead.

When serializing the segment on disk, we will need to iterate over the sorted terms,

and for each of these terms, we need to iterate over the sorted docids that contain this term.

The first prototype of tantivy was simply using a BTreeMap<String, Vec<u32>> to do this job.

The code would go through the document one by one, and:

- increment the doc id

- tokenize the document

- for each token, look for the posting list (

Vec<u32>) associated with the term and append theDocIdto each of the posting lists.

The code probably looked something like this.

fn tokenize<'a>(text: &'a str) -> impl Iterator<Item=&'a str> {

// ...

}

struct SegmentWriter {

num_docs: u32,

inverted_index: BTreeMap<String, Vec<u32>>,

}

impl SegmentWriter {

pub fn add_document(&mut self, document: &str) {

// `DocId` are allocated by auto-incrementing

let doc_id = self.num_docs;

for token in tokenize(document) {

self

.inverted_index.entry(token.to_string())

.or_insert(vec!())

.push(doc_id)

}

self.num_docs += 1;

}

}I call this task stacking, as it feels like we are trying to

push DocIds to stacks associated with each term.

For simplification, I omitted term frequencies and term positions. Depending on the indexing options, we may also need to keep the term frequencies and the term positions.

If we index term frequencies, then the Vec<u32> above will contain a lasagna of doc_id_1, term_freq_1, doc_id_2, term_freq_2, etc.

If we index positions as well, then the Vec<u32> will also contain the term position as follows,

doc_id, term_freq, position1, …, position_termfreq .

No more BTreemap

The current version of tantivy is slightly more complicated than BtreeMap.

First, since we only need the terms to be sorted when the segment is flushed to disk, it is better to use a HashMap and just sort the terms at the very end.

An ad-hoc HashMap

So we will focus on a hash map implementation that fills the following contract:

- We should reduce the time spent in memory allocation and copies as much as possible.

- The hash should be only computed once per token

- As long as the hash differ, we should jump at most three times in memory to stack our

DocId.

The standard library HashMap does not make it possible to fill that contract, so I had to implement a rudimentary HashMap.

Using a memory arena

Indexing will require a lot of allocations. It might be interesting to make those as fast as possible by using an ad-hoc memory arena with a bump allocator.

Also, a memory arena makes it trivial to enforce the user-defined memory budget we discussed earlier.

This memory budget is split between the threads. Then, for each thread, the memory budget is split between the hash table and the size of the memory arena (roughly with the ratio 1/3, 2/3). After inserting each document, we simply check if the hash table is reaching saturation or if the memory arena is getting close to its limit. If it is, we finalize the segment being written.

This memory arena does not offer any API to deallocate objects. We just wipe it clean entirely Magna doodle style after finalizing the segment and before starting a new segment.

Location, location, location

Stacking -or building this postings list- requires jumping in memory quite a lot. By jumping, I mean accessing a random memory address that is likely to trigger any kind of cache miss.

The array used to store the buckets of the HashMap cannot reasonably include our keys as they have a variable length. Instead, each bucket contains the pair:

(hash: u32, addr: u32)

An empty bucket is simply expressed using the special value addr==u32::max_value().

When the bucket is not empty, addr is the address, in the memory arena at which both the key and the value are stored,

one after the other, as follows:

- the length of the key (2 bytes)

- the key (variable length)

- an object that represents the posting list object (24 bytes).

Keeping the key and the value contiguous in the memory arena, not only saves us from having two addresses, it also gives us better memory locality.

You might be surprised that the posting list is fixed. Its size is constant in the same sense that our original Vec object was Sized. It simply includes pointers to other areas in the memory arena. Let’s dive into the details.

Exponential unrolled linked list

We cannot reimplement Vec over our memory arena.

When it reaches capacity a Vec allocates twice its capacity, copies its previous data, and finally deallocates its previous data. Unfortunately, our MemoryArena does not allow for deallocation. Also, we do not really care about having fast random access. We only read our values when our segment is serialized to disk, so we are satisfied with a decent sequential access.

Unrolled linked list is a common data-structure to address this problem. If like me you are not too familiar with data-structure terminology, an unrolled linked list is simply a linked list of blocks of B values.

Assuming a block size of B, iterating over an unrolled linked list of N elements now requires N / B jump in memory.

Of course, the last block may not be full, but we will waste at most 4 * (B - 1) bytes of memory per term (the 4 is there because we are storing u32).

Choosing a good value of B is a bit tricky. Ideally, we would like a large B for terms that are extremely frequent, and we would like a small B for a dataset where there are many terms associated with few documents.

Instead of choosing a specific value, tantivy uses the same trick as Vec here, and allocates blocks that are exponentially bigger and bigger.

Each new block is twice as big as the previous block.

That way, we know that we are wasting at most half of the memory.

We also require only log_(N) jumps in memory to go through a long posting list of N elements.

In addition, in order to further optimize for terms that belong to a single document, the first 3 elements are inlined with the value, so that our posting list object looks like this.

struct ExpUnrolledLinkedList {

len: u32,

end: u32,

// -- inlined first block

val0: u32,

val1: u32,

val2: u32,

// -- pointer to the next block

next: u32,

}

end contains the address of the tail of our list. It is useful when adding a new element to the list.

len is also required in order to detect when a new block should be created.

next is a pointer to the second block. It is useful when iterating through the list, as we serialize our segment.

A block of size N simply consists of 4*N bytes to encode the N u32-values, followed by 4 bytes to store the address of its successor.

Which hash function?

At this point, profiling showed that the major part of the time is spent hashing our terms.

I tested a bunch of hash functions. Previous versions of tantivy were using djb2 which has the benefit of being fast and simple.

It performed really well on the Wikipedia dataset, but not as well on the Movielens dataset. Movielens is a dataset of movie reviews and it includes a lot of close to unique terms, like userIds.

More precisely, I noticed that indexing a segment was relatively fast at the beginning of the segment. But as the hash table was getting more saturated, indexing would get slower and slower.

I naturally suspected that we were suffering from collisions.

There is really two kind of collisions:

-

two keys are mapped to the same bucket, in which case testing the equality of the hash key in the hash table should help to identify that we need to find another bucket using a probing method that has an ok locality (

tantivyuses quadratic probing). This happens very frequently. The frequency is precisely equal to the saturation of our hash table. -

two keys are different but have the same hash, in which case tantivy has to check for string equality. This requires painfully jumping in memory and comparing the two strings.

Assuming a good 32-bits hash key, the rate at which these collisions should happen is of roughly K / 2^32, where K is the number of keys inserted so far (In fact slightly less than this but this is a good approximation). So if we have 1 million terms in our segment, this should happen at a rate of roughly 1 out of 4000 new terms inserted.

Unfortunately, by construction, djb2 tend to generate

way more hash collisions for short terms.

I tried different crates offering implementation of various hash and ended up settling for a short rust reimplementation of murmurhash32. Problem solved!

Benchmark

English Wikipedia contains 5 millions documents (8GB).

In my benchmark, I did not store any of the fields, and the text and the title of the article are indexed with their positions. There is no stemming enabled, and we only lowercase our terms. I also disabled segment merging, so we are really measuring raw indexing speed.

The Wikipedia articles are read from a regular hard drive, but the index itself is written on a separate SSD disk.

My desktop has 4 cores with hyperthreading. I have no faith in hyperthreading so I only displayed the results for up to 4 indexing threads. If I increase the number of threads, it decreases a bit more down to 80 seconds. Here is the result of this benchmark :

4 threads, 8 gigabytes, 94s is not too shabby, isn’t it? That’s around 300GB / hour on an outdated desktop.

In comparison, the first version of tantivy would take 40mn to index Wikipedia on my desktop, without merging any segments.

Giving honest figures with segment merging enabled is a bit tricky. Scheduling merges is a bit like scheduling pit stops in a formula 1 race. There is a lot of room to tweak it and get better figures.

That being said, count between 3 minutes and 4 minutes to get an index with between 2 and 8 segments and a memory budget of between 4GB and 8GB.

Conclusion

Tantivy 0.4.0 is already very fast at indexing.

I did try to compare its performance with Lucene, but simply decoding utf-8 and reading lines from my file took over 60 seconds in Java. That did not seem like a fair match: remember it took 94 seconds to tantivy to read the file, decode JSON, and build a search index for the same amount of data. I was too lazy to work out a binary format to palliate Java’s suckiness and do a proper comparison with Lucene indexing performance.

While there is still room for improvement, the next version of tantivy will focus on adding a proper text processing pipeline (tokenization, stemming, removing stop words, etc.). tantivy is getting rapidly close to a decent search engine solution.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also want to have a look at this blog post from JDemler that explains how index building is done in another rust search engine project called Perlin.