Of tantivy, a search engine in Rust

Foreword. Search. Rust.

I have been working more or less with search engines since 2010. Since then, I entertained the idea to try and code my own search engine. I ended up never starting this project, but accumulated more and more information over the year about how to implement a search engine, mostly by learning from coworkers, going through Lucene’s code, and reading academic papers and blogs.

Last year, after hearing a lot of good things about Rust from an old friend and then a coworker, I started studying the language. I was very skeptical in the beginning, but the Rust book sold me rapidly. As I went through its pages, I learnt how Rust was solving all of the pain points I experienced with C++ or Java with mindblowing elegance.

I then started going through all of the exercises on exercism.io. The exercises are well calibrated and introduce new concepts gradually, if you want to try and learn Rust, I warmly recommend them, and it should only take your around a week-end. After finishing the exercises, I decided it was time to go out for a test drive on a real-life project. I started working on a simple search engine…

Mildly relevant obscure Japanese reference (PPAP)

Mildly relevant obscure Japanese reference (PPAP)

Around two weeks later, to my own surprise, I was more productive in Rust than I was in C++ in which I have 5 years of experience. Don’t get me wrong. I am not saying Rust is a simple language. I was not an expert in Rust at that time, nor am I an expert in Rust today… But Rust is just a much more productive language. Also, while my code was sometimes clumsy, I felt a degree of confidence that my code was not buggy, that I had never experienced in any other language (Well, my experience of OCaml is so tiny it does not count).

The first version was a bit silly but only took a couple of months of my spare time to implement. Next step was to actually refactor, clean up the rookie mistakes, add documentation… tantivy was born.

The logo is so neat, you can feel it’s webscale.

The logo is so neat, you can feel it’s webscale.

But this blog post is not about my experience with rust, but about how tantivy works.

Tantivy is strongly inspired by Lucene, and if you are a Lucene user, this will sound incredibly familiar… Like Lucene, Tantivy is a search engine library and does not address the problem of distribution. Making a proper distributed search engine that scales, would require to add an extra layer around tantivy, playing the role of what ElasticSearch or Solr are to Lucene.

So what happens when I search?

Imagine that you indexed wikipedia with tantivy, as described in tantivy-cli’s tutorial for instance.

Let’s go through what happens when you search for President Obama on this index, and receive the 10 most relevant documents as a result.

This will introduce the datastructures at stake, before we eventually dive into the details.

This blog post will not describe how the index is built as it will be the subject of the part 2.

Query Parser

First, the user query President Obama goes through the query parser, which will transform it into something more structured. For instance, depending on your configuration, the query could be transformed into (title:president OR body:president) AND (title:obama OR body:obama). In other words, we want any document that contains the word president and the word obama regardless of whether they are in the body field or the title field. Obviously, a document having “President Obama” in its title field is probably more relevant and should appear at the top, but we will rely on scoring for that.

Following Lucene’s terminology, the couples field:text (e.g. (title, obama)) are called Terms in tantivy.

Term dictionary (.term file)

We now have a boolean query with 4 terms. We first lookup all of these terms in a datastructure called the term dictionary. For each of the term, it associates the following information :

- the number of documents containing the term (also called document frequency)

- a pointer (or an address) into the inverted index file

Inverted index (.idx file)

The inverted index has its own separate file. It contains, for each term, a sorted list of document ids. Such a list is usually called inverted list, postings, or posting list. The pointer that was given to us from the term dictionary is simply an offset within this file.

Note that I haven't explained what is a document id. For the moment, just consider them as an incremental internal id identifying a document. I will tell you more about what they are in part 2.

We can start and read in parallel all of these inverted lists. Since they are sorted, computing the relevant intersections and unions can be done very efficiently.

Currently I have put very little effort in optimizing this part. Whatever the number of terms involved (well, if there is more than one), and whatever the boolean formula, tantivy will compute the union of the terms using a simple binary-heap k-way merge, and post filter the result. There is therefore still a lot of room for improvement.

At this point, we have an iterator over the doc ids over the document that match our initial boolean query. But they are sorted by doc ids, ad what we really want is the top 10 most relevant docs.

We will go through this iterator entirely, and for each doc id, compute a relevance score for each document. We then push all of the pairs (DocId, Score) to a collector object. The collector is

in charge of retaining the ten documents with the highest score. This can be done simply using a heap.

Scoring

Tantivy relevance score is a flavor of the very classical Tf-Idf. I won’t get into the detail, but Tf-Idf expresses a distance between the query and documents. Its computation involves to know for each term of the query :

- the document frequency - that is the number of document containing the term. It was given in our term dictionary.

- the term frequency - the number of occurences of the term within the document. As we will see, it is actually encoded within the inverted index file, interlaced in blocks with the doc ids.

- the number of terms in each field for the document. This is how we know that being in the title field is more important than being in the body field. A dedicated file and datastructure is storing our fieldnorm.

Doc store (.store)

After having scored all of our documents, we are then left with a list of winning DocIds. We finally fetch the actual content of our documents in a datastructure called the doc store.

Index files, and Directory

So far, we talked about four big component of tantivy

- the term dictionary

- the inverted index

- the doc store

- the field norms

Each of them is stored in its own file.

There are in fact two other type of files : the fast fields and the position files, but they are not useful for this type of query.

Tantivy embraces the write-once-read-many (WORM) concept. This means that all of these files are written once and for all, and can then be considered read-only. This does not mean that you cannot add any documents. This will all be explained in the next part.

Like in Lucene, writing and reading these files is actually

abstracted by a Directory trait. By default, tantivy is meant to be used with the MmapDirectory in which File are actual files on disk, and are accessed via “mmap”.

Tantivy does not require to load any data structure in anonymous memory, so that when used with the MmapDirectory, tantivy resident memory footprint is extremely low.

This is actually a very nice feature.

Since page cache is shared, n servers reading the same index consumes about as much RAM as a single server.

Deploying a new version, or running two instances for AB-testing, has close to zero impact on memory usage.

Tantivy can also easily work on indexes that do not fit entirely in RAM.

The OS will be in charge to decide which pages are the most useful.

Finally, Tantivy has a very small loading time, and is perfect for a command line interface usage.

Tantivy also comes with another Directory implementation called RAMDirectory which stores all of the data in anonymous memory, and is mostly useful when writing unit test.

As we will see, the IO required in search are mostly sequential and there might be a use case for more exotic directories. Hitting on HDFS, or an HTTP interface for instance…

Tantivy’s file interface is however very different than that of Lucene in that it let’s the user take a slice out of the file, and then access a byte array (&[u8]) from it.

It is up to the client of the directory to behave responsibly and avoid asking for gigantic slices of data. The current version of tantivy is not behaving great for the moment unfortunately, and this should be improved in the future.

Implementing a directory implementation is quite subtle as we need to ensure that writes are persistent and that at least some writes must be atomic. You can have a look at its contract in the reference documentation .

The term dictionary

The term dictionary is arguably one of the most complicated data structure to code in a search engine. While using a hash map might come to mind, it is often handy to be able to enumerate terms in a sorted manner. For this reason, Trie and Finite state transducers (FST) are popular data structures for search engine’s term dictionary. Rust is blessed with a great implementation of FST by BurntSushi, so this was a no brainer for tantivy.

Recent version of Lucene also use an FST, while earlier version of Lucene used a Trie. FST are more compact than Tries and they are only a tad more CPU intensive. You can read more about FST on BurntSushi’s blog post.

Inverted index

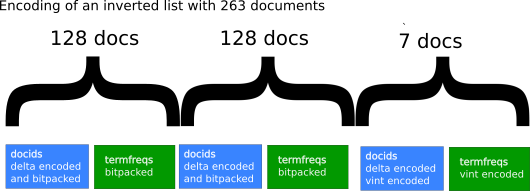

Because we want to make sure that most of our data fits in RAM, and to reduce the amount of data read from RAM and possibly disk, it is crucial to compress our lists of integers. Let’s describe the way tantivy represents our posting lists.

Doc ids and term frequencies are encoded together, in interlaced blocks of 128 documents. That way, as we iterate through our inverted list, we don’t have to jump between two lists. A block of 128 doc ids is followed by a block of 128 term frequencies.

The block of 128 term frequencies, are simply encoded using bit packing : for instance, assuming the largest value in the block is 10, we really only need 4 bits to encode each of the term frequency, as 2^4 - 1 = 16 >= 10. Bit packing simply means we use the first to express how many

bits are used in our representation (here 10), and then we concatenate the 4 bits representation of our 128 integers. As a result,

1 + (4 * 128) / 8 = 65 bytes is required for the storage of our document frequencies.

Doc ids on the other hand are sorted. We therefore start by delta-encoding them. We replace the list of doc ids by the consecutive intervals between them.

For instance, assuming the document id list goes

7, 12, 15, 17, 25

We encode it as 7, 5, 3, 2, 8

The resulting deltas can then be bitpacked.

Our last block is very likely to contain less than 128 documents. In that case, we use variable-length integer in place of bitpacking.

By default, these operations are actually not implemented in tantivy, but delegated to a state-of-the-art C++ library called simdcomp using SIMD instructions.

Because some platform do not handle SIMD instruction, this is actually a Cargo feature, that can be disabled by compiling tantivy with --no-default-features. Tantivy then uses a pure rust SIMD-free implementation of this encoding.

Field norms

The field norm file contain the field norms for all the fields and all of the document in the index.

For each document, the difference between the field norm and the minimum field norm is simply bitpacked in order to make random access possible.

Doc Store

Once we have identified the list of doc ids that must be returned to the user, we still need to fetch the actual content the documents to the user.

Tantivy’s docstore is very similar to Lucene’s doc store. For each document, the subset of the fields’s that have been configured as stored in your index schema are serialized and appended to a buffer of data. Once the buffer exceeds 16KB, it is compressed and written on disk.

Choosing a lossless compression algorithm is a matter of picking the right speed / compression ratio trade-off for your use case. Tantivy uses LZ4, which sits on the very fast compression/decompression, but not so compact side of the spectrum.

Obviously we still need to identify the block in which our document belong to. The store file also embed a skip list that associates the last doc id of each block to the start of the next block.

This index makes it easy to identify in which block a doc id belongs. The whole block is then decompressed and the document pulled out.

For many usage it can be a good idea to decouple the doc store part from the search index, and possibly use an external KV store or database of your choice for this. Decoupling hardware doing search on one hand and fetching documents on the other hand can drastically lower the overall amount of RAM required for your architecture.

Also, as we will see in the part 2 of this blog post, updating a document in a search engine is not instantaneous. Imagine a search engine for a newspaper, you might want to be able to correct a typo in an article instantaneously while users not finding the article when searching the mistyped word for a few minutes is not an issue at all.

Nevertheless, tantivy is meant to come with batteries included, and therefore includes a doc store which should do just fine for many use cases!

Wrapping up…

In the next blog post, I will tell you how tantivy’s index are built.

In the meanwhile, if you are interested in the project, you can check out the

GitHub repository page.

The README.md gives a bunch of pointer on how to get started.

If you want to contribute, or discuss a use case with me, feel free to comment or drop me email.