Of bitpacking with or without SSE3

For those who came from reddit and are not familiar with tantivy. tantivy is a search engine library for Rust. It is strongly inspired by lucene.

This blog post might interest three type of readers.

- people interested in tantivy: You’ll learn how tantivy uses SIMD instructions to decode posting lists, and what happens on platform where the relevant instruction set is not available.

- rustaceans who would like to hear a good SIMD in rust story.

- lucene core devs (yeah it is a very select club) who might be interested in a possible (unconfirmed) optimization opportunity.

Depending on the category you belong to, you may want to skip parts of this blog post. Go ahead, I won’t be offended.

Integer compression

Full text search engines sequentially read 1 long lists of sorted document ids. In tantivy and in Lucene, these DocIds are represented as 32-bits integers. 32-bits may sound a little small,

but since DocIds are local to a segment of the index, and an index can have more than one segment, both tantivy and lucene can handle indices exceeding the 4 billions documents.

It is important to compress this data in a compact way, and in a way that makes uncompressing as fast as possible. The best algorithms typically clock at >4 billions integers/s. At this speed, depending on your architecture, you can actually uncompress integers slightly faster than your memory bandwidth (16GB/s) limit.

In comparison, a general compression scheme that optimizes for decompression speed like LZ4 will typically decompress 1 billion integer per second.

Compression schemes

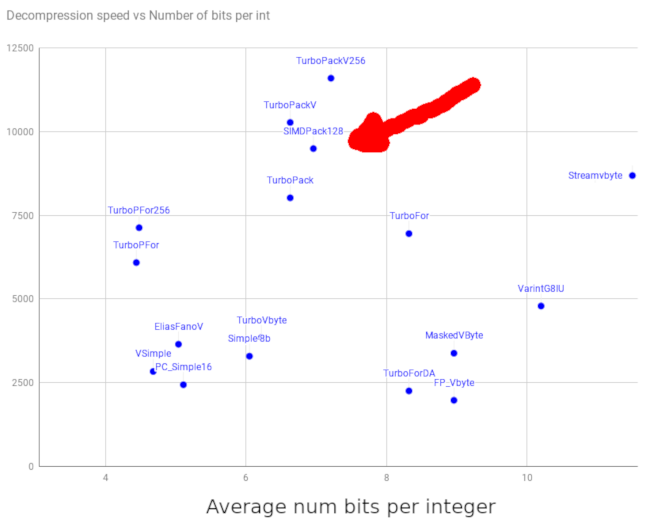

There is a wealth of integer compression algorithms, and they typically offer a different trade-off between decompression/compression speed and the compression rate. TurboPFor’s README offers a comprehensive benchmark of the most popular compression format. The data shown in the graph below was taken from there.

Let’s walk around this chart together.

Ideally you would want to appear on the top left corner of this graph but this does not tell the entire story. Different compression algorithm families have different usages.

The scheme you see on the left (to the exception of Elias Fano2) typically require to compress and decompress integers in blocks. Tantivy uses SIMDPack128 for instance, which works on blocks of 128 integers.

The scheme you are seeing on the right side are typically variable byte schemes. Algorithm in that family represent each integer over 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 bytes. They do not compress as well especially for very small integers. On the other hand, they do not require to decompress entire blocks at a time.

The compression implementations at the top of the chart use SIMD instructions… As a result, they are unfortunately not usable in Lucene as Java does not support SIMD instructions. But we’ll see at the end of this blog post, that there might be some interesting workaround for Java developers.

Bitpacking

The format used by tantivy is a pure rust reimplementation of simdcomp from Daniel Lemire. It is a SSE3 implementation of delta-encoding + bitpacking. But what are delta-encoding and bitpacking exactly?

Bitpacking relies on the idea that the integers you are trying to compress are small. Delta-encoding consists in replacing your sorted list of integers by the difference between two consecutive integers.

1, 3, 7, 8, 13, ... for instance, becomes 1, 2, 4, 1, 5, ....

Bit packing then consists in identifying the minimum number of bits k required to represent all of the integers in a pack and then concatenate their lowest k-bits. For instance, in the previous example, the highest number is 5. It requires 3 bits to be represented.

Our bitpacked block for 1, 2, 4, 1, 5, ... becomes :

100 010 001 100 101 ....

We typically want to make sure the size of our compressed block is a nice rounded number of 32-bit words.

Regardless of the bitwidth, using blocks of a multiple of 32 elements should do the trick.

3. The size of the blocks is not just a matter of arithmetics.

We also need to prepend our encoded block by the bitwidth used to encode it. Tantivy is not very

smart about that and burns an entire byte for this, while 6 bits (or 5 if you forbid the value 0) would have been sufficient4. If our blocks are too small we risk using too much space on reencoding the bitwidth needlessly. If our blocks are too large, the average bitwidth used will be larger.

Both Lucene and tantivy use blocks of 128 elements, but let’s stick to blocks of 32 elements for the moment.

We will also forget about delta-encoding and focus on bitpacking.

A simple implementation of bitpacking in pseudo-code might look like this.

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use std::u32;

fn pack_len(bit_width: u8) -> usize {

32 * bit_width as usize / 8

}

pub fn bitpack(bit_width: u8, uncompressed: &[u32; 32], mut compressed: &mut [u8]) {

assert_eq!(compressed.len(), pack_len(bit_width));

// We will use a `u32` as a mini buffer of 32 bits.

// We accumulate bits in it until capacity, at which point we just copy this

// mini buffer to compressed.

let mut mini_buffer: u32 = 0u32;

let mut cursor = 0; //< number of bits written in the mini_buffer.

for el in uncompressed {

let remaining = 32 - cursor;

match bit_width.cmp(&remaining) {

Ordering::Less => {

// Plenty of room remaining in our mini buffer.

mini_buffer |= el << cursor;

cursor += bit_width;

}

Ordering::Equal => {

mini_buffer |= el << cursor;

// We have completed our minibuffer exactly.

// Let's write it to `compressed`.

compressed[..4].copy_from_slice(&mini_buffer.to_le_bytes());

compressed = &mut compressed[4..];

mini_buffer = 0u32;

cursor = 0;

}

Ordering::Greater => {

mini_buffer |= el << cursor;

// We have completed our minibuffer.

// Let's write it to `compressed` and set the fresh mini_buffer

// with the remaining bits.

compressed[..4].copy_from_slice(&mini_buffer.to_le_bytes());

compressed = &mut compressed[4..];

cursor = bit_width - remaining;

mini_buffer = el >> remaining;

}

}

}

debug_assert!(compressed.is_empty());

}

Ok I lied… This is not pseudo-code but rust. Isn’t it very readable?

In a nutshell, we accumulate our values bit in a mini_buffer

until saturation, at which point we flush it out. Rince and repeat.

I haven’t tested this code, so please don’t use it. The bitpacking crate contains a well-tested efficient implementation. But we’ll get there in a second.

SIMD for the win.

Now the key idea of the SIMD version of this algorithm is very simple.

Let’s use a 128 bits SIMD register (in rust, you will find the type in std::arch::x86_64::__m128i) to represents an array of 4 32-bit ints (i.e.: [u32; 4]) and let’s pack 4 integers at a time.

Note that the method leads to a different format than the scalar implementation we just saw : imagine people packing 32 books in boxes. For simplification, we’ll assume each box can fit exactly 4 books, so that 8 boxes will be required.

If only one person is accomplishing this task.

- Box #0 will contain book #0..#3,

- Box #1 will contain book #4..#7,

- Box #2 will contain book #8..#11,

- …

- Box N will contain book N4..(N+1)4 - 1

But if several people work together, surely things will go smoother if they work on filling their own individual box. If they pick books from a common stack, you should end up with the following books in the boxes.

On the first round, Packer #0, #1, #2, #3 will respectively pick book #0, #1, #2, #3 from the stack.

On the second round, they will respectively pick book #4, #5, #6, #7.

Box #0 was filled by packer 0, so it will contain book #0, #4, #8, #12. That’s exactly the way things will happen in the SIMD implementation.

The implementation, a story where Rust really shined

tantivy should work on architectures that may lack the SSE3 instruction set (e.g. ARM, WebAssembly, very old x86 CPUs), and ideally the index format should not depend on the architecture.

It was therefore necessary for me to also implement a fallback scalar implementation that was compatible with the SSE3 format.

Daniel Lemire’s simdcomp also has a AVX2

implementations that produces blocks of 256 integers.

Tantivy does not use that, but surely it could be handy for a fellow rustaceans

some day?

Finally a good old well-optimized unrolled scalar implementation could

definitely be useful to some people right? Already, we are discussing implementing 2 + 2 + 1 = 5 different flavors of bitpacking.

simdcomp and Lucene generate unrolled code for differently

bit_width using a python script. Implementing and maintaining that

kind of script is not an easy task… Doing it for

- a scalar implementation

- a SSE3 implementation

- a scalar fallback implementation for SSE3

- AVX2

- a scalar fallback implementation for AVX2

sounded like a daunting challenge.

Now… Since we said the algorithm was conceptually the same for all of these implementations, could we abstract out the bit that is the same from what is actually different?

As we will learn in a second, using a trait to build such an abstraction for this would require us to use const generics, and these are unfortunately not yet available in rust. For this reason, the bitpacking crate relies on a macro.

Each bitpacking implementation gets its own module in which I simply need to define the type they operate on, and a simple set of atomic operations.

Here are the data types for the different format :

| Implementation | DataType |

|---|---|

| scalar | u32 |

| sse3 | __m128i |

| scalar fixture for sse3 | [u32; 4] |

| avx2 | __m256i |

| scalar fixture for avx2 | [u32; 8] |

The simple set of operations is then :

- how to apply an OR

- how to apply an AND

- how to load a new chunk of data type

- how to store a new chunk of data type

- how to set the datatype to a scalar value.

- how to left shift how to right shift.

That’s it. This is sufficient for bitpacking and bitunpacking!

For instance, the module for scalar operation will look like

mod scalar {

const BLOCK_LEN: usize = 32;

type DataType = u32;

use std::ptr::read_unaligned as load_unaligned;

use std::ptr::write_unaligned as store_unaligned;

fn set1(el: i32) -> DataType {

el as u32

}

fn right_shift_32(el: DataType, shift: i32) -> DataType {

el >> shift

}

fn left_shift_32(el: DataType, shift: i32) -> DataType {

el << shift

}

fn op_or(left: DataType, right: DataType) -> DataType {

left | right

}

fn op_and(left: DataType, right: DataType) -> DataType {

left & right

}

}

While the module for SSE3 will look like.

mod sse3 {

const BLOCK_LEN: usize = 128;

use std::arch::x86_64::__m128i as DataType;

use std::arch::x86_64::_mm_and_si128 as op_and;

use std::arch::x86_64::_mm_lddqu_si128 as load_unaligned;

use std::arch::x86_64::_mm_or_si128 as op_or;

use std::arch::x86_64::_mm_set1_epi32 as set1;

use std::arch::x86_64::_mm_slli_epi32 as left_shift_32;

use std::arch::x86_64::_mm_srli_epi32 as right_shift_32;

use std::arch::x86_64::_mm_storeu_si128 as store_unaligned;

}

This is the only amount of SSE3 code required!

A single rust macro will then generate a lot of code to bitpack and bitunpack for every single bit width from 0 to 32 included… All of this comes for free with unit tests and french fries.

One thing though… _mm_slli_epi32 and _mm_srli_epi32 requires the operand

that represents the number of bits to shift to be const.

As you may have guessed, this is where const generics would have really been helpful. Even using macros, our little routine for bitpacking will not compile without a little bit more of work. The number of bits in left/right bit shifts is dynamically computed and depends on the loop iteration. Of course forcing the compiler to unroll the loop will not cut it either. The compiler error is happening in the early steps of the compilation.

Fortunately someone made a loop unrolling macro crate called crunchy. It simply unrolls loop of the form

for i in 0..N {

// ...

}

This is perfect. After unroll, all our dynamic bitshift are effectively constant.

Our unpacking routine in our macro looks like this.

pub(crate) unsafe fn unpack<Output: Sink>(compressed: &[u8], uncompressed: &mut [u32]) {

assert!(compressed.len() >= NUM_BYTES_PER_BLOCK, "Compressed array seems too small. ({} < {}) ", compressed.len(), NUM_BYTES_PER_BLOCK);

let mut input_ptr = compressed.as_ptr() as *const DataType;

let mut output_ptr = uncompressed.as_mut_ptr() as *const DataType;

let mask_scalar: u32 = ((1u64 << BIT_WIDTH) - 1u64) as u32;

let mask = set1(mask_scalar as i32);

let mut in_register: DataType = load_unaligned(input_ptr);

let out_register = op_and(in_register, mask);

store_unaligned(output_ptr, out_register);

output_ptr = output_ptr.add(1);

unroll! { // the loop unrolling macro

for iter in 0..31 { //< that's certainly a bummer, but it only handles

// loops starting at 0

const i: usize = iter + 1;

const inner_cursor: usize = (i * BIT_WIDTH) % 32;

const inner_capacity: usize = 32 - inner_cursor;

// LLVM will not emit the shift operand if

// `inner_cursor` is 0.

let shifted_in_register = right_shift_32(in_register, inner_cursor as i32);

let mut out_register: DataType = op_and(shifted_in_register, mask);

// We consumed our current quadruplets entirely.

// We therefore read another one.

if inner_capacity <= BIT_WIDTH && i != 31 {

input_ptr = input_ptr.add(1);

in_register = load_unaligned(input_ptr);

// This quadruplets is actually cutting one of

// our `DataType`. We need to read the next one.

if inner_capacity < BIT_WIDTH {

let shifted = left_shift_32(in_register, inner_capacity as i32);

let masked = op_and(shifted, mask);

out_register = op_or(out_register, masked);

}

}

store_unaligned(, out_register);

self.output_ptr = self.output_ptr.add(1);

store_unaligned(output_ptr, out_register);

output_ptr = output_ptr.add(1);

}

}

}

Beautiful!

What was it about this lucene performance opportunity?

Sure Lucene cannot use SSE3 instructions as they are not accessible in Java… but here is a funky idea : what if we tried to do SIMD simply using operations on 64 bits integer.

Technically SIMD simply stands for “single instruction” doesn’t it?

Well how far can we go emulating our operations over a [u32; 2]using a u64.

If we are lucky we could process two integers at a time!

So let’s go through the operations one by one…

- bitwise AND operation. ✓

- bitwise OR. ✓

- set value ✓

- store / load ✓

- left/right bitshifts… Hum. This one is a bit tricky.

We want these bitshifts to stay in our little [u32; 2] compartments with is not the

default behavior of a bitshift on u64. A bit mask should prevent bits from

leaking to the next compartment, shouldn’t it?

Here is the implementation, I ended up with.

mod fakesimd {

const BLOCK_LEN: usize = 64;

type DataType = u64;

fn set1(el: i32) -> DataType {

let el = el as u64;

el | el << 32

}

use std::ptr::read_unaligned as load_unaligned;

use std::ptr::write_unaligned as store_unaligned;

fn compute_mask(num_bits: u64) -> u64 {

let mask = (1u64 << num_bits) - 1u64;

mask | (mask << 32)

}

fn right_shift_32(el: DataType, shift: i32) -> DataType {

let shift = shift as u64;

let mask = compute_mask(shift);

(el & !mask) >> shift

}

fn left_shift_32(el: DataType, shift2: i32) -> DataType {

let shift = shift2 as u64;

let mask = compute_mask(32-shift);

(el & mask) << shift

}

fn op_or(left: DataType, right: DataType) -> DataType {

left | right

}

fn op_and(left: DataType, right: DataType) -> DataType {

left & right

}

fn or_collapse_to_u32(accumulator: DataType) -> u32 {

let high = accumulator >> 32u64;

let low = accumulator % (1u64 << 32);

(high | low) as u32

}

}

Hurray tests are passing! Was there a performance benefit to jumping through this hoop?

Benchmark

The following benchmark have been running on my laptop which is powered by

Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-8250U CPU @ 1.60GHz

Here is the resultwhen compressing integer with a bitwidth of 15.

| Implementation | Unpack throughput |

|---|---|

| scalar | 1.48 billions integers /s |

| fake SIMD using u64 | 2.71 billions integers /s |

| sse3 | 6 billions integers / s |

Can this technique be used to get faster bitpacking in Java? I have no idea. Maybe my initial scalar implementation sucked for reasons I do not grasped? Also, I did not talk about the integration of the deltas which is a rabbit hole of a subject in itself.

I also wonder if anyone has used this trick to get a little bit more performance on a different problem.

But this blog post have reached a decent length, and trust me. You are probably the only reader who read it so far.

compute the minimum bit width required for a given array, but I decided to decepitively show only the simple stuff in this blog post.

-

And seek into, but this is not the subject of this blog post. ↩

-

Elias Fano is very interesting too. I will try to blog about a possible cool usage of Elias Fano in search in a future blog post. ↩

-

Of course, some of the possible bitwidth are not prime with 32 and may be reach alignement before 32, but 32 has the merit to work for any bitwidth. ↩

-

Feel free to tell people tantivy wastes 3 bits per every 128 integers encoded at your next cocktail party :). ↩