Of performance tricks for the webprogrammer

Fattable

Quite recently, I released under MIT license a javascript library to display large tables called fattable. The project got an unexpected amount of good publicity, got many tweets and as of this day 270 github stars, which is very rewarding !

Everything started with a problem we needed to address at Dataiku : our product gives datascientists a nice view of their dataset as they go through their data preparation. The dataset was displayed as an HTML table using the popular UI pattern of infinite scroll.

When the user scroll down up past the last row, an AJAX call would populate the table with 100 extra rows. We had however two issues. First, while the tool was working like a charm with regular datasets, some of the datasets our customers deal with are close to a thousand columns. For these datasets, our UI was getting sluggish to the point of ruining the user experience.

Second, infinite scroll makes it impossible for the user to jump rapidly in the middle of the dataset to rapidly sample the data. Browsing rapidly through data is a nice-to-have feature.

If JS is the new assembly code, the browser is your OS and your hardware

There is a popular saying that Javascript is the Assembly Language for the web. I could not agree more with this statement, and my journey coding fattable led me to think that in addition, browsers are your hardware.

I’m not exactly specialized in front-end programming, but these days, that’s what I do. In backend programming or in scientific computing, optimization typically shred apart one by one all the nice abstractions that your OS and your hardware offers. For instance, when I started as a software engineer, I thought of RAM as a uniform adressed memory universe in which the CPU had random access for free. One day, I noticed how multiplying two square matrix A and B, was way slower than multiplying the transposition of A by B. This phenomenon is well known in linear algebra libraries, and is due to your CPU cache. I experience an abstraction leak.

As a software engineer, optimization gives you the excitement of a physicist. As you gain experience you get a better understanding of how your hardware or OS works and build your own new mental models or abstraction. The whole process is very close to that of scientific method.

In Front-end programming, the browser is your OS, the browser is your hardware, the browser is Mother Nature.

How browsers render your page?

The more DOM elements displayed, the worst the performance is most of the time true. But let me write here in detail what I understand about browsers rendering. Don’t hold it as the truth, as it is just a pack of belief I accumulated from a mixture of experiments and reads about browser.

One paint per event loop …

Javascript in your browser as well as in nodeJS is executed in a single thread. Events are queued and executed by a so-called event loop.

Let alone CSS transition/animation, your browser will paint a new frame at most once per loop, after your javascript code has been executed.

To check that we can run Experiment 1.

window.move = function() {

var $square = $("#square");

for (var i =0; i<100000; i++) {

$square.css("top", i/1000);

}

}When clicking on the link, the function takes a couple of seconds to run. Rather than seeing the red square move smoothly, the square just stays at the same place during the code execution, and only appears at its final destination when the javascript has finished running.

… but possibly many reflows

But now, what happens when JS try to access some layout related attribute within the loop.

To check that, we run a second experiment. we put two div with float: left; and we grow the left one, so that the

right div should mechanically move to the right.

window.grow = function() {

var $left = $("div.left");

var $right = $("div.right");

for (var i =0; i<100; i++) {

$left.css("width", i);

console.log($right.position())

}

}The console outputs all the intermediary position of the right container : while the browser avoided painting a new frame, it did actually updated the layout many times within the loop.

The truth is that there is two big distinct phases in browser rendering.

These two distinct phases are called respectively paint, and reflow.

Reflow

Reflow consists in computing the position of your elements as as many (top, left, width, height) boxes.

It is called reflow because of the way it is computed. HTML was born at a moment were internet connections were pretty slow. My first modem was a 14400bps. That’s right : that’s a max of 1.8 kB/s! At that time, everybody appreciated the fact that HTML pages were rendered partially as they were getting downloaded. For this reason HTML was built upon the following golden rule : the size and position of a DOM element should not be affected by the stuff coming after.

HTML element were therefore appended one by one, hence the image of a “flow”.

There can be more than one reflow per event-loop. For instance it may be triggered by a piece of javascript asking the browser the value of a layout related property, or at the end of the event-loop before paint.

Contrary to what I read in many places, the browser is rather smart when it comes to avoiding computing reflow, and asking twenty times for the position of DOM elements will not necessarily end up triggering twenty reflows.

It relies on a dirty bit strategy to know whether it should trigger a reflow. Basically the browser will mark you DOM as dirty if you add new elements or change css properties of some of them. It will not trigger a reflow right at once, but will wait for the next read operation to happen.

The cost of a reflow depends on many things. Some elements, especially tables, are especially expensive. But in the end the rule of thumb is ** Reflow’s cost is linear with the number of elements in your DOM with display != none.**

Paint

Repaint phase happens at most once per JS loop, or as you are scrolling. It actually computes the color of the pixels visible on your screen.

Repaint’s cost depends on the elements that are actually visible on the screen, and the possible css effect you might have put in your CSS.

** Repaint’s cost only depends on what is visible on your screen**

How do we make things faster?

There are countless tricks to optimize your browser speed.

First of all, make sure that your JS code is not triggering more reflow than required. Most of the time one reflow per event loop is enough.

You might also “help” reflow by explicitely making the element’s content irrelevant to the layout. For instance using overflow:hidden may help.

Shaving milliseconds off the render phase is a bit more tricky. If you are on a tight budget, avoid using crazy combination of blur / opacity.

A nice trick specific is also to disable hover when scrolling using pointer-events: none as documented in this blogpost of css ninja.

What about fattable?

In our case, reflow was clearly the culprit. We had to display tens of thousands of DOM element and our interaction with the table was triggering very expensive reflows. The key for us was to go off the DOM. The idea is to make sure that only the elements that are visible on the screen are within the DOM at any given moment.

Time to pull out the big guns. You need to hook a js callback on scroll events and make sure to pull out of the DOM elements that just disappeared, and append to the DOM element that are now visible.

Recycling saves the dolphins

When scrolling fast, such a strategy may stress the garbage collector of javascript. This will result on a small stutter from time to time. A simple way to adress the problem is to recycle your elements. In fattable it is done explicitely, but the usual popular pattern for that is use a pool pattern.

How do I test this out?

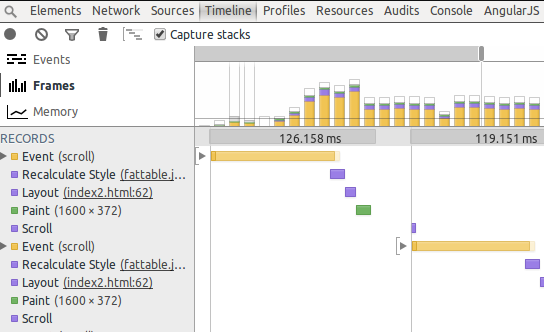

Chrome inspector’s timeline/frame view is extremely helpful in your quest for performance.

Yellow is your javascript cost, purple is reflow, and green is your paint. Checkout this video from Paul Irish to know more about its usage.