Of the pearl puzzle

Comparison sort complexity

In my first post I dropped a line about 525 being the theoretical minimal number of comparison required to sort a list of 100 elements without explaining it. I will do so here, and show how the same thought process can help solving the 12 pearls puzzle.

Let’s got through a thought experiment.

Let’s imagine you are playing a game with a friend.

You are locked in a room and your friend is outside, holding a randomly shuffled deck of cards marked with numbers ranging from 1 to N. You have a similar deck of card, but sorted.

Your goal is to put it in the same order as the deck of your friend. The only questions you can ask him are of the form “is the card at position #6 shows a bigger number than the card at the position #29?” and the guy from the other side will answer you by yes or no.

We assume you are a very reasonable person and that you are asking your questions determiniscally. In other words, if you played the game a second time, you would ask the same questions as long you got the same answers.

Let’s have you play the game a LOT of times, we could log in a book the shuffle of the cards and the answers you got for each questions. The book would look something like :

[ 3, 17, 29, 12, ..., 15 ]: Yes No Yes Yes No No Yes

For two different shuffle, you cannot possibly have gotten the exact same series of answer, because if it was so, you wouldn’t had enough information to discriminate between the two shuffle when you were playing.

In other words, if you were to play all the possible n! (factorial n) shuffle, you would have gotten n!- different series of answers.

Now let’s call C the highest number of questions you had to ask

to finish a game. 2C is an upper bound for the number of series of answer you had. We therefore have

The algorithm you ran as you were playing is called a comparison sort. C is the worst-case complexity of your algorithm.

Apply the log to the inequation leads us to

How smart could you be, you will never be able to think about a strategy for which you can sort out your deck of card in less than

log_2 (n!) questions all the time.

This result is usually presented as the best possible complexity for a comparison sort is n ln n.

This can be shown very easily by using the Stirling formula.

In the rest of this post, I’ll try to show that this kind of reasonning can actually help solving problems the 12 pearls puzzle.

The 12 pearls puzzle

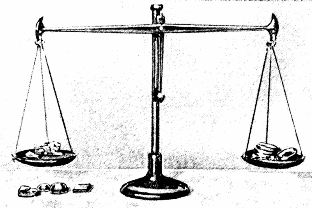

You’ve been given 12 pearls and a balance scale like the one in the picture. It has two plates, and you can compare the weight of the things you put on each plates.

One of the pearl is fake, and you don’t know which one. All pearls have the very same weight, except for the fake one which is either heavier or lighter (and you don’t know which).

The problem consists of finding out which pearls is fake and whether it is heavier of lighter, by using the balance scale at most three times.

Three times can’t be enough?

Spoiler alert. If like me, you like puzzles, you might want to stop reading now, and come back after you solved it.

The problem is intentionnally misleading. You might think that the balance gives you only two outputs : “heavier” or “lighter”.

If it was so, using the same argument as before, we can show that using the balance three times will make it only possible to discriminate within 23=8 configurations.

But in this problem, your answer consists of identifying the fake pearl (12 candidates) and whether it is lighter or heavier. The problems has 24 possible different answers, which is greater than 8.

The first trick is to notice that such a balance has a ternary output. It may tell you that the objects on both plates have the exact same weight. That’s 33=27 which is greater than 24.

Finding out the first weighting with no sweat

Now let’s consider the first weighting. First we reject the possibility of putting a different number of pearls in each plate, as it doesn’t much information if the balance goes in the direction of bigger number.

The first weighting will be of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 pearls on each plate.

Let’s show how a simple reasonning will let us get rid of some of these options. After this first weighting, we will have only 2 shot to find our pearls. With two weighting we can at most discriminate between 32 = 9 possibilities.

For 1, 2, 3, if the scale tells us that the two plates have equal weights, we will only know that the fake pearl is within the remaining 10, 8, 6 pearls. We won’t have any info about the fake pearl being heavier or lighter either. That’s respectively 20, 16, or 12 possible answers. We won’t be able to discriminate that many answer with only 2 weighting. 1,2,3 are therefore not an option.

Now let’s consider weighting 5 pearls against 5 pearls, or 6 pearls against 6 pearls. If the scale outputs that the left plate is heavier than the right plate, we will be sticked with the possibilities that either the fake pearl is within the left plate and is heavier, (respectively 5 and 6 possibilities) or that the fake pearl is in the right plate and is lighter than the other pearls (respectively 5 and 6 possibilities). Overall we will have to discriminate between 10 or 12 possibilities with two weighting, which is impossible.

We haven’t explored any of the possibilities, yet we showed that the only possible first move is to weight 4 pearls against 4 other pearls !

A naive implementation

Let’s now try to write an algorithm that solves this problem for n pearls. More accurately, it will return, given n, the minimal number of measures to solve the problem for n pearls. The first implementation will be very naive and have a complexity I honestly don’t want to think about. It will help however to give some reality to some of the concept I talked about.

We will go through all possible weighting, while keeping a list of all the remaining answer that are still possible. For each weighting we will consider the new list of possible configurations if we get each of the three output from the scale… A bit like you would do in a game of Guess Who?. We keep a list of all the possible answers, and ask questions and depending on the answer of the questions, we get rid of the solutions one by one.

# let's call that the naive implementation!

from itertools import combinations

from collections import defaultdict

def measure(pearl_weights, left, right):

# returns the result of a measure.

left_weight = sum(pearl_weights[i] for i in left)

right_weight = sum(pearl_weights[i] for i in right)

return cmp(left_weight, right_weight)

def measures(n):

# generator yielding all the possible way

# to select 2 set of k pearls

# to put on the plates of the scale

for nb_pearls in range(1,n/2+1):

for pearls_involved in combinations(range(n), nb_pearls*2):

pearls_involved_set = set(pearls_involved)

for left in combinations(pearls_involved, nb_pearls):

right = pearls_involved_set.difference(left)

yield (left, right)

def populations_after_measures(population, n):

# loops on the possible way to make a measure

# and yield list of the three populations

# matching with the 3 possible outcome of

# the scale

for (left, right) in measures(n):

measure_results = defaultdict(list)

for configuration in population:

measure_output = measure(configuration, left, right)

measure_results[measure_output].append(configuration)

if len(measure_results) > 1:

yield measure_results.values()

def browse_solutions(population, n):

for branches in populations_after_measures(population, n):

yield max(

solve(branch_population, n)

for branch_population in branches

)

def solve(population, n):

if len(population) == 1:

return 0

else:

solutions = browse_solutions(population, n)

return 1 + min(solutions)

def pearl_problem(n):

if n <= 2:

return None

population = []

for i in range(n):

pearl_weights = [0] * n

pearl_weights[i] = 1

population.append(tuple(pearl_weights))

pearl_weights[i] = -1 # negative weight haha!

population.append(tuple(pearl_weights))

return solve(population, n)Cutting branches

With the naive implementation, things are going reaaallllly slow starting n=5. It is slow because recursive calls themselves perform recursive calls and so on.

Your program is like running through a gigantic tree. And how do you get gigantic trees thinner? You cut its branches of course.

One simple way to cut branches for instance, would be to let the different calls know about the current best result. That way, as soon as they detect they won’t be able to beat the high score, they can just stop exploring this branch. I won’t implement this optimization here. What I am going to do is return results directly if I reached a theoretical minimum. If I find a solution that finds our fake pearl in ceil(log_3(len(population))) measures, then I can just stop exploring sibling branches.

# let's call that the "cutting branches"

# implementation!

from itertools import combinations

from collections import defaultdict

from math import ceil, log

def measure(pearl_weights, left, right):

# returns the result of a measure.

left_weight = sum(pearl_weights[i] for i in left)

right_weight = sum(pearl_weights[i] for i in right)

return cmp(left_weight, right_weight)

def measures(n):

# generator yielding all the possible way

# to select 2 set of k pearls

# to put on the plates of the scale

pearls = range(n)

for nb_pearls in range(1,n/2+1):

for pearls_involved in combinations(pearls, nb_pearls*2):

pearls_involved_set = set(pearls_involved)

for left in combinations(pearls_involved, nb_pearls):

right = pearls_involved_set.difference(left)

yield (left, right)

def populations_after_measures(population, n):

for (left, right) in measures(n):

measure_results = defaultdict(list)

for configuration in population:

measure_output = measure(configuration, left, right)

measure_results[measure_output].append(configuration)

if len(measure_results) > 1:

yield measure_results.values()

def browse_solutions(population, n):

for branches in populations_after_measures(population, n):

yield max(

solve(branch_population, n)

for branch_population in branches

)

def min_with_limit(g, limit):

res = g.next()

for x in g:

res = min(res, x)

if res<=limit:

return res

return res

def solve(population, n):

if len(population) == 1:

return 0

else:

limit = ceil(log(len(population),3))-1

solutions = browse_solutions(population, n)

return 1 + min_with_limit(solutions, limit)

def pearl_problem(n):

if n <= 2:

return None

population = []

for i in range(n):

pearl_weights = [0] * n

pearl_weights[i] = 1

population.append(tuple(pearl_weights))

pearl_weights[i] = -1 # negative weight haha!

population.append(tuple(pearl_weights))

return solve(population, n)Not much has changed right? Our algorithm performs slightly better. We can now compute in 15s the solution of our problem for n=7. We still cannot solve our initial problem, which is for n=12.

How can we do it better?

A good trick is to try to cut branches as soon as possible. In our cases, it would be nice to check start exploring the branch that are more promising first. That way if there is a perfect answer we will find it sooner.

To do so we only need to tune our population after measures method. We will sort it in order to have the measures splitting the population as evenly as possible first.

# let's call that the "cutting sooner"

# implementation!

def populations_after_measures(population, n):

branches = []

for (left, right) in measures(n):

measure_results = defaultdict(list)

for configuration in population:

measure_output = measure(configuration, left, right)

measure_results[measure_output].append(configuration)

if len(measure_results) > 1:

branches.append(measure_results.values())

return sorted(branches, key=lambda x:max(map(len, x)))That doesn’t look like to promising, but it is actually a huge improvement on the previous algorithm. We can now solve our problem for 12 pearls!

So let’s sum up what we did here! We cut branches by returning results if we have some way to know they are optimal. We try to find those optimal faster by going through the most promising ones first. We also saw but didn’t implement the fact that stopping as soon as we detect we won’t be able to do as well as our siblings.

Being more human

Still, people solve this problem right? They’re definitely doing something smarter than this, or it would take them days to find the solution.

I think the difference lies the way our brain pictures a population and the way the previous algorithm does. My brain doesn’t consider all the combinations like we do here, but understands how pearl 1 and pearl 2 are playing symmetric roles.

For the last algorithm we will try to sum up a population by a tuple (n,l,h,r) where

- n is the number of pearls for which we don’t know anything

- l is the number of pearls for which we know that if they are fake, they are heavier

- h is the number of pearls for which we know that if they are fake, they are lighter

- r is the number of pearls for which we know that they are real.

This greatly reduce the number of branch in our tree. In addition, the space of the possible arguments with which solve is called with is small enought to cache the results.

(I erased the previous mention of an implementation which was not as performant as the one below, and a lot more difficult to understand.)

The other great benefits is that it makes it a mathematical object which is much easier to grasp.

Let’s call c(n,l,h,r) the function that gives us the minimum number of weighting required by the best strategy possible.

We will also call p the function of our initial problem, that is :

.

With some good coffee, paper and pen it is actually easy to prove that there exists a solution to solve the pearl problem for n=3k in k+1 weightings.

In terms of our function p, we have

That’s actually a very strong result because, as we have shown it before, we also know that

Applying the log, we can get very tight boundaries for c(3k) :

.

This interval actually contains only one integer, we have proven that :

It is also possible to show that the function c is increasing, so that for all n,

So for all n, we actually have only two possible values. Surely we can use that for optimization! Imagine that : as soon as we get a solution with a cost of the lower bound we can return, as soon as we show that a solution will not reach the lower bound we can return.

Here goes the implemementation :

from math import floor, log

# Let's call that the "smart" algorithm

"""In this implementation we represent our knowledge

on the pearls as a quadruplet (n,h,l,r) where

* n is the number pearls for which we don't

know anything.

* h is the number pearls for which we know

that if they are fake, they must be heavier

than the real pearls.

* l is the number of pearls for which we know

that if they are fake they must be lighter

than the real pearls

* r is the number of pearls for which we know they are real.

"""

def diff(pop_a, pop_b):

return tuple(a-b for (a,b) in zip(pop_a,pop_b))

def add(*pops):

return tuple(sum(els) for els in zip(*pops))

def minus(pop):

return tuple(-el for el in pop)

def heavier(pop):

(anything, light, heavy, real) = pop

return (0, 0, heavy + anything, real + light)

def lighter(pop):

(anything, light, heavy, real) = pop

return (0, light + anything, 0, real + heavy)

def even(pop):

return (0, 0, 0, sum(pop))

def population_after_measures(population, measure):

"""Given a population and a measure, returns

the three resulting populations, depending on

the outcome of the measure.

"""

(left, right) = measure

pop_no_weighted = add(population, minus(left), minus(right))

# if the balance says the two plates are even

yield add(pop_no_weighted, even(left), even(right))

O = sum(pop_no_weighted)

# if the balance says the left plate is lighter

yield add( lighter(left), heavier(right), (0,0,0,O) )

# if the balance says the left plate is heavier

yield add( heavier(left), lighter(right), (0,0,0,O) )

def nb_of_answers(pop):

""" Returns the number of possible

answer given a population.

"""

return pop[0]*2 + pop[1] + pop[2]

def fill_plate(pop, plate_size):

""" Yields all the possible sub population

of plate_size pearls within pop.

"""

head,tail = pop[0], pop[1:]

if len(pop)==1:

if head >= plate_size:

yield (plate_size,)

else:

for i in range(min(plate_size,pop[0])+1):

for fill_remaining in fill_plate(tail, plate_size-i):

yield (i,) + fill_remaining

def measures(pop):

""" Returns all possible normalized.

measures for a given population.

A measure is described as a couple (left, right)

where left is the population to put in the left

plate and right is the population to put in the

right plate.

Since (left,right) is equivalent to

(right, left), we only yield measures for

which left >= right

"""

N = sum(pop) # the number of pearls

possible_plate_sizes = range(1, N/2+1)

for plate_size in possible_plate_sizes:

for left in fill_plate(pop, plate_size):

remaining = diff(pop, left)

for right in fill_plate(remaining, plate_size):

if left >= right:

yield (left, right)

def solved(pop):

return pop[0]==0 and sum(pop[1:3]) <= 1

def solve(pop, m):

"""Returns True if the pearl problem

of the population pop can be solved

in less than m measures.

To do so, apart from the special cases

we test all possible measures.

If one measure makes it possible to

solve the problem in m, we return m.

If one outcome of one measure gives

a result greater than m-1, we

test the next measure.

"""

if m < 0:

return False

if solved(pop):

return True

if 3**m < nb_of_answers(pop):

# we will never be able to

# reach the limit of m

# because of the information

# argument

return False

(n,l,h,r) = pop

if l<h:

return solve((n,h,l,r), m)

for measure in measures(pop):

for pops_branch in population_after_measures(pop, measure):

if not solve(pops_branch, m-1):

break

else:

return True

return False

def pearl_smart(n):

if n<3:

return None

pop = (n, 0, 0, 0)

# our solution is either m

# or m+1

m = int(floor(log(n, 3)))+1

if solve(pop, m):

return m

else:

return m+1

if __name__ == "__main__":

assert pearl_smart(3) == 2

assert pearl_smart(12) == 3

assert pearl_smart(13) == 4Results, because everyone loves a colorful graph.

Here is the running time of the algorithm for the different implementation.

As you can see the “smart” is doing way better than the other implementation.

Interestingly the computational of the smart implementation is not an increasing function of the number of pearls. If we plot it for a bigger