Of tantivy indexing datastructure, the stacker

For those who came from reddit and are not familiar with tantivy. tantivy is a search engine library for Rust. It is strongly inspired by lucene.

Things tantivy does differently

Some developers have a strange aversion to reading other project source code. I am not sure if this is the sequel of the school system, where this would be called cheating, or if it is a side-effect of people taking pride in viewing programming as a “creative” job.

I think this approach to software development is suboptimal to say the least.

It is not a secret : Tantivy is very heavily inspired by Lucene’s design and implementation. Whenever I have a doubt about how to implement something, I dive into books and other search engines implementation and I always treat Lucene as the default solution. It would be stupid to do otherwise : Lucene is simply the most battle-tested opensource search engine implementation.

There are however a couple of parts where I knowingly decided to do things differently than lucene… Some of these solutions are a little bit original, in that I have never seen them used before. If someone else happen to like these ideas, I’d love it if people came and apply them somewhere else.

I hope I will be able to find time in the future to describe these ideas one by one, but let’s be honest: my life has been very busy lately, and it is fairly difficult for me to find time to blog.

In this first post, I will describe a datastructure that is at the core of tantivy’s indexer and differs from what I have seen so far. I suspect it could be helpful in very different contexts, to build a real time search/reverse search engine, to implement a map-reduce engine more efficiently, sort a log into user sessions, implement an alternative sort -k, etc.

The problem we are trying to solve : Building an inverted index efficiently.

Most search engine rely on a central datastructure called an inverted index.

For the sake of simplification, let’s consider documents consists of a single text field, and are identified by a DocId.

Each document’s text is split into a sequence of words. We call those words tokens and the splitting operation tokenization. The inverted index is just like the index at the end of a book. For each token, it associates the list of document ids containing that token. This list of document is also called a posting list.

In other words, your set of document might look like

doc1 -> [life, is, a, moderately, good, play, with, a, badly, written, third, act]

doc2 -> [life, is, a, long, process, of, getting, tired]

doc3 -> [life, is, not, so, bad, if, you, have, plenty, of, luck,...]

...

and your inverted index looks like :

play -> [1]

plenty -> [3]

luck -> [3]

process -> [2]

life -> [1,2,3]

is -> [1,2,3]

a -> [1,2]

moderately -> [1]

...

As explained in previous blogposts ([part 1] and [part 2]), tantivy’s inverted index representation is extremely compact and efficient… but it is immutable.

Tantivy’s indexing process itself requires some mutable in-RAM datastructure.

A HashMap<String, Vec<DocId>>, above would be a decent candidate for this job.

Our indexing function would then look as follows.

use std::collections::HashMap;

pub type DocId = u32;

pub type InvertedIndex = HashMap<String, Vec<DocId>>;

fn tokenize(text: &str) -> impl Iterator<Item=&str> {

text.split_whitespace()

}

pub fn build_index<'a, Corpus: Iterator<Item=(DocId, &'a str)>>(corpus: Corpus) -> InvertedIndex {

let mut inverted_index = InvertedIndex::default();

for (doc_id, doc_text) in corpus {

for token in tokenize(doc_text) {

inverted_index

.entry(token.to_string())

.or_insert_with(Vec::new)

.push(doc_id);

}

}

inverted_index

}

As we append documents to this mutable/in-RAM datastructure, we need to detect when it reaches some user defined memory budget, pause indexing, and serialize this datastructure to our more compact & efficient on disk index format.

In reality, depending on our schema, we record more information per term occurence than simply DocId. We might for instance record the term frequency and the positions of the term in the document. Also, in order to stay memory efficient, these DocIds are somewhat compressed. This is not much of a problem, we can generalize our solution by exchanging our HashMap<String, Vec<DocId>> for a HashMap<String, Vec<u8>>.

In the end, our problem can be summed up as, how can we maintain and write efficiently into tens of thousands of buffers at the same time.

Specifications for our problem

Let’s sum up our specifications, to see where we can improve on our original HashMap solution.

First, we need to know our memory usage accurately. Tantivy’s API let’s the user specify a memory budget and it is tantivy’s duty to stick to it. That way, tantivy can index datasets of any size (I already indexed corpuses of 5TB on a 8GB RAM machine) without swapping. This is extremely comfortable for the user.

Second, our memory usage should be a slim fit for all terms.

We cannot really make an assumption about the distribution of document frequency of our terms. When indexing text, we will typically reach tens of thousands of terms before we decide to flush the segment. Word frequency typically follow a Zipf’s law. Frequent words will be very frequent and their associated buffer will be very large. However a lot of rare words will appear only once and will require a tiny buffer. We need to be sure our solution is a tight fit for everyone of them.

When indexing logs, we will also reach a lot of extrems depending on the field: timestamps may be unique, while an AB-test group or a country could be heavily saturated.

Third, we do not care about reading our buffers until we start serializing our index… And at that point, we only read our data sequentially.

Fourth, we never delete any data and we release all our memory at the same time. The pattern in which we populate our HashMap is very simple. We only insert new terms, and never delete any. We only append new data to posting lists. All memory is released in bulk at the very end.

Behold, the stacker

I called tantivy’s solution to this problem the “stacker”.

You probably guessed it, we will put all of our data in a memory arena. Using a memory arena will remove the overhead associated to allocating memory, and deallocation will be as fast and simple as wiping off a magna doodle. Also, we will keep a super accurate idea of the memory usage.

We cannot free memory anymore though. Vec<u8> are not a viable solution anymore,

as we would not be able to reclaim its memory after it is resized. Instead, a common solution could be to use an unrolled linked list. The problem with unrolled linked lists is that choosing the size of our blocks is a very complicated problem. If our blocks are too large, space will be wasted for rare terms. If blocks are too small, then reading the more frequent terms will require to jump in memory a lot. We would love to have large blocks for frequent terms, and small blacks for rare terms.

Vec’s’ resize policy had an elegant solution to that problem. Doubling the capacity everytime Vec reaches its limit guaranteed us that at most 50% of the memory is wasted.

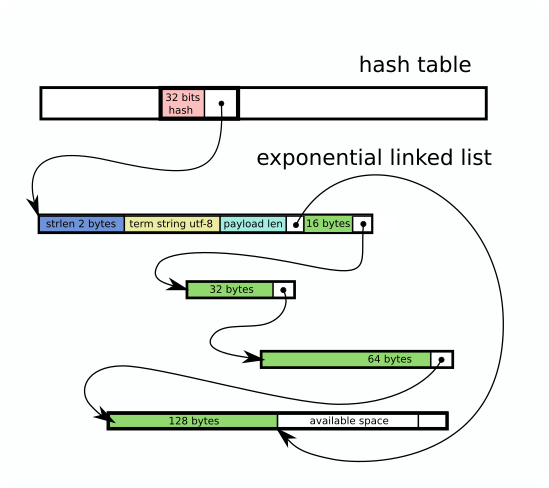

Tantivy’s stacker takes the best of both worlds. We keep the benefit of unrolled linked list and Vec by using blocks growing exponentially in size. The first block has a capacity of 16 bytes, the second block has a size of 32, and then it goes 64B, 128B, 256B, 512B, 1KB, 4KB, 8KB, 16KB, 32KB above which it stagnates.

This way, depending on the payload, we remain somewhere in between 50% and 100% of memory utility.

Implementation details.

- The memory arena also makes it possible to rely on 32bits address instead of full-width pointers.

- The hashmap is not shaped like usual hashmaps that have a String as a key. Each bucket only contains the hash key (currently 32-bits), and an address in the arena. The arena contains the key length (over 16-bits) followed by the key bytes, followed by the first block of our exponential unrolled linked list. This improves the locality between the key and the value, while keeping the table itself as lean as possible.

It also makes it possible for me to store all fields in the same hashmap, even though they require values of different types.